I don’t speak Irish. Like almost every Irish kid I was taught it at school, but in my case this was interrupted when my parents moved overseas. Not much scope for learning the Irish language in a British school in Greece in the 1980s. That said, upon my return home to Dublin several decades later I can’t say my Irish is significantly worse than most of my contemporaries. It seems like few of my generation retained the language… even though most of them had daily lessons in the subject right up to the age of 16.

That’s not intended as a criticism of the Irish language. It’s not even intended as a criticism of teaching or promoting it (though it suggests that if we do wish to increase the number of Irish speakers; whatever the hell the Irish Board of education was up to in the 1970s and 80s should be avoided like the plague). Rather it’s just to illustrate the fact that it’s not something I feel strongly about. If you’re a Gaeilgeoir and that annoys you… I’m sorry; it is what it is.

I think it’d be very sad if the Irish language died out. More than that; if a strategy was developed (either in the schools or some as-yet undreamt-of community initiative) that was demonstrated to significantly increase the number of people voluntarily learning and speaking Irish, I’d genuinely celebrate it (for all sorts of reasons) and would have no issue with the government funding it. I’m not a strict utilitarian when it comes to public spending… so long as we do a half-decent job of trying to cover the essentials, a society should also try to fund those things, within reason, that are culturally important to it.

If you’re a libertarian and that appalls you, don’t worry; your views will change quite a lot when you grow up.

But again, let me stress, if I was shaping Sinn Féin / Republican policy in Northern Ireland right now, an Irish Language Act would not be one of my red lines. If I was them I’d be doubling-down on the “look how moderate and reasonable we’ve become” strategy, all the while quietly putting their faith in the inevitability of a unification referendum after Brexit tanks the British economy. Once they’re part of a united Ireland they can rejoice in their children sharing the same experience as those down south… that of resentfully learning a language they’re destined to immediately forget upon graduation.

Instant Retraction!

Did I just say an Irish Language Act would not be one of my red lines? I take it back.

No seriously, I retract that. Total U-Turn. In fact, I’d go so far as to suggest that an Irish Language Act is now of primary importance for the formation of any power-sharing government in Northern Ireland. It’s a massive red line. And it is rightfully a massive red line.

There is an effort in the UK media to portray this impasse as Sinn Féin digging their heels in about a trivial issue. Or worse, something that is simultaneously trivial and explosively sectarian. And when I say the UK media, I don’t just mean the usual suspects.

The Mail, The Sun, The Express… they are all predictably predictable. But it was reading The Guardian’s shocking editorial on the subject that I felt genuine anger. Here we have the editorial position of what is ostensibly the newspaper of Britain’s liberal left, and it is either a shamefully ill-researched slab of ignorance or it’s a knowing hatchet-job on Irish republicanism.

I want you to ponder this line from that editorial…

“The darker truth here is that Sinn Féin has chosen to weaponise the language question for political ends, less to protect a minority than to antagonise unionists.”

That’s not the darker truth here. Let me explain the darker truth here… and in the off-chance the author of that Guardian editorial is reading this, I will try to use small words.

No Angels

Sinn Féin are perfectly capable of trying to make political hay out of any situation. That’s what politicians do. But the darker truth here is that a promise is being reneged upon. And I don’t care which side does it; it’s completely unacceptable. It would be just as bad if the DUP were being painted as unreasonable and aggressive (“weaponising language”) simply for holding Sinn Féin to what they already signed-up to. Pretty sure the editor of The Guardian would have no problem with that. Right?

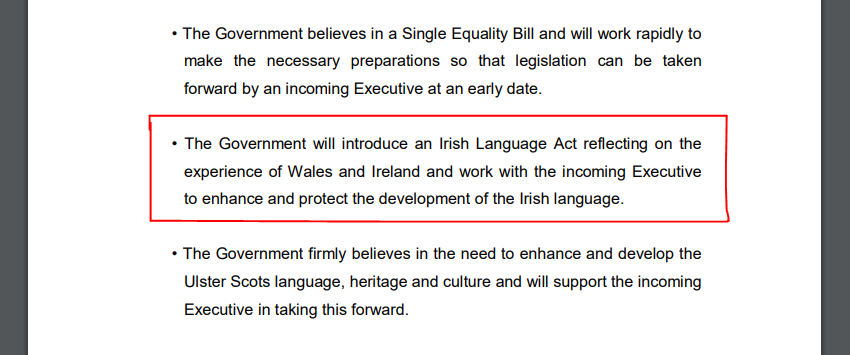

More than a decade ago, Unionists, Republicans, the Irish and British governments all gathered in Scotland. At St. Andrews, they revised and eventually agreed the rules by which the Stormont power-sharing executive would function. This included both procedural aspects and legislative ones. Among the promises made by all present was the following…

(You can download the full text of the St. Andrews Agreement as a PDF from the UK government’s website. That paragraph appears in Annex B.)

The text that finally made it into actual British legislation — Northern Ireland (St Andrews Agreement) Act 2006 — isn’t as explicit, demanding instead that “a strategy be developed” […] “to enhance and protect the development of the Irish language.”

Weasel words?

So the DUP points to the Northern Ireland (St Andrews Agreement) Act 2006 and insists (technically correctly) that it doesn’t explicitly commit them to an Irish Language Act.

But that British law is not what all parties agreed and signed at St. Andrews. That piece of paper, the St. Andrews agreement itself, between the DUP and Sinn Féin (amongst others) clearly and explicitly promises an Irish Language Act. And that’s the context we find this whole farrago unfolding within.

It’s not about the Irish language. It’s about one side, one community, being told it doesn’t need to honour its commitments. And the other being painted as antagonistic when they call foul. Britain’s attitude towards Ireland has become deeply disturbing. On one side we have the editor of The Guardian openly suggesting the DUP can pick and choose which former agreements they need to abide to, while a senior sitting Tory MP (and former minister) suggests that maybe the entire Good Friday Agreement be jettisoned…

The collapse of power-sharing in Northern Ireland shows the Good Friday Agreement has outlived its use https://t.co/Qc72wysJpr @RuthDE via @Telegraph. @NIOgov

— Owen Paterson MP (@OwenPaterson) February 16, 2018

Culturally speaking, I don’t understand what the hell is going on in Britain right now. I feel bad for my UK friends who largely seem as mystified as I am, but I also fear for the collateral damage this whole British psychotic episode might have on us here. Ireland is a million miles from the country I remember from the 1970s, but I’m far from convinced “the peace process” is 100% finished yet. And it would be sheer lunacy to start picking at that scab now.

I’m aware that the Irish Language Act is not the only obstacle to the resumption of power-sharing. But even if it was, it’s not something that can be compromised on. As soon as you say one party to an agreement does not have to uphold their promise, there is zero chance power-sharing can have a future.